You've been a smart kid and you've studied hard. Your law (or medical) degree is testimony to your commitment to science and humanity and the long client list is indisputable proof that you are good in your field of expertise.

But deep down in your heart you know you could have done much better devoting your life to politics, watchmaking, or even the noble and fine art of second hand dealing. The question is: do you have what it takes to call yourself a watchmaker? Are you just a dreamer or a rough but flawless diamond with an impeccable eye for detail?

Before you get too excited about changing career, it is my responsibility to assess whether you have what it takes. In other words, are you really "watchmaker material"?

Here we go.

This is a real life example. No tricks, just straight forward thinking.

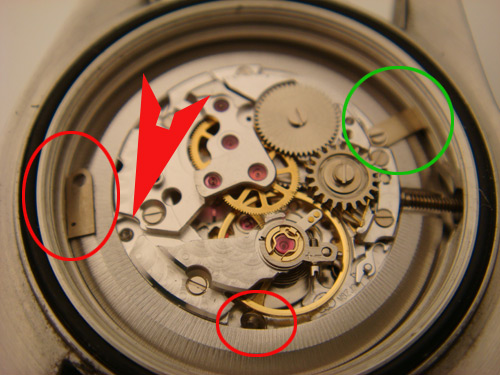

The photo below shows a ladies' Tudor watch. The watch was sold 2 years ago and back then it was in brand new, unworn condition. Returned to us this week with a note stating "it stopped". The case back was removed as well as the auto winding system, for clarity.

1. Can you see what is *obviously* wrong with this watch?

2. What caused the mechanism to stop?

3. What needs to be done to return the watch to good working order?

4. How long would it take to rectify the problem?

5. How much should we charge the customer?

I'll give you just one tip: the watch does not need an overhaul/service, just one very specific repair.

Please don't give up too easily. The answer is below, but if you jump to the answer without giving it a try, you'll kick your bottom and you will say, wow this was too obvious.

You won't find the answer as the fifth most important question online because this is something you should work out on your own and tell me .

--------------------------------------------------------

The problem described above is one of the most common reasons for malfunction found in a wrist watch. Yet it has severe consequences to performance: complete 'denial of service'.

1. Shown on the right (circled in green) is the movement case clamp. It is held in place with a screw. The purpose of the clamp is to hold the mechanism firmly inside the watch case.

The clamp on the left side (red) got itself detached because the watch head snapped off. 2. The screw head then lodged itself underneath the balance wheel and caused the watch to stop. The good thing: it was clearly exposed for easy removal. If it went further (deeper) into the gear train, the mechanism would need complete disassembly.

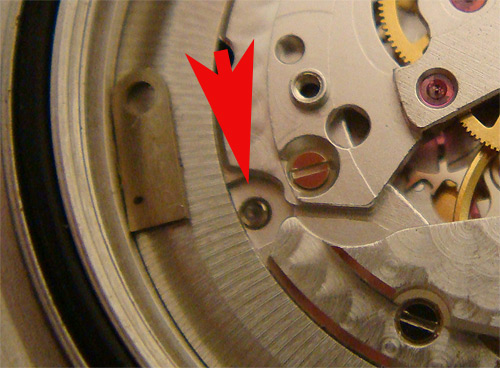

However, before the new screw could be installed, the below part of the body need to be extracted.

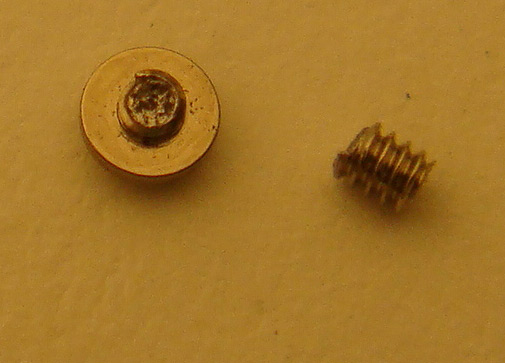

In this particular case, extraction was straight forward because the thread was not damaged.

The reason why the screw head snapped: under higher magnification, the screw body appeared to be flawed, and some impurity in the metal structure is clearly visible.

The screw hole after extraction:

3. clamp re-installed, new screw.

The watch was checked for time keeping (and a minor adjustment was required). The balance wheel was not affected and the auto-winding system with the rotor was reinstalled.

4. Thanks to an easy extraction, the entire repair took approx. 15 minutes.

The broken casing clam screw is often the result of excessive external force (for example, the watch being dropped) Over tightening or an in-built flaw could also be a contributing factor.

5. How much to charge? To determine the cost of the repair, one should take into account many factors: difficulty and complexity of the repair, availability of spare parts and total 'bench' time, including overall turn-around time for the watch to be returned to the customer. Another determining factor is what a watch manufacturer (Rolex) would charge for a similar repair.

What do you think would be a fair and correct amount to charge?

As we always say, happy collecting!

No comments:

Post a Comment